Adding more value-embeddings to modded-nanogpt led me to an (as of yet unofficial) modded-nanogpt medium record as seen in PR#119.

In this article, I present these results, and a lot more ablations of experiments that didn’t work out. Here’s a table of contents:

- What are value embeddings?

- The record

- Adding value embeddings

- Removing value embeddings

- Shifting value embeddings

- Sharing value embeddings differently

You can find the reproducible code at this link.

What are value embeddings?

In modded-nanogpt, there are multiple embedding layers. There is, of course, the input embedding which jumpstarts the residual, and which is transformed through the transformer layers. But there are also the value embeddings.

They are applied inside the attention block. Specifically, an embedding-module is used to produce embeddings from the token IDs, and those embeddings are then added to the values in the attention module. Simplified, this is how this looks in code:

def attention_with_value_embeddings(

input_ids: torch.Tensor, # B, T

x: torch.Tensor, # B, T, D

value_emb: nn.Embedding,

lambdas: torch.Tensor, # 2

W_q: nn.Parameter, # D, D

W_k: nn.Parameter, # D, D

W_v: nn.Parameter, # D, D

) -> torch.Tensor:

q = rope(F.linear(x, W_q))

k = rope(F.linear(x, W_k))

v = F.linear(x, W_v)

### Here come the value embeddings

v_embs = value_emb(input_ids) # B, T, D

v = lambdas[0] * v + lambdas[1] * v_embs # <- add value embeddings to values

### ------------------------------

... # apply attention

The lambdas are learned scalar weights. I will continue calling them “lambdas” throughout this article.

It’s important to note that the value embeddings are shared between multiple layers. In the baseline, there are three value embedding-modules; each produces embeddings that are used in two layers:

- One applied to layers 0 and 13

- One applied to layers 1 and 14

- One applied to layers 2 and 15

The record

I have added two more value embeddings to the model, so that the five total value embeddings are now applied in the following way:

- One applied to layers 0 and 11

- One applied to layers 1 and 12

- One applied to layers 2 and 13

- One applied to layers 3 and 14

- One applied to layers 4 and 15

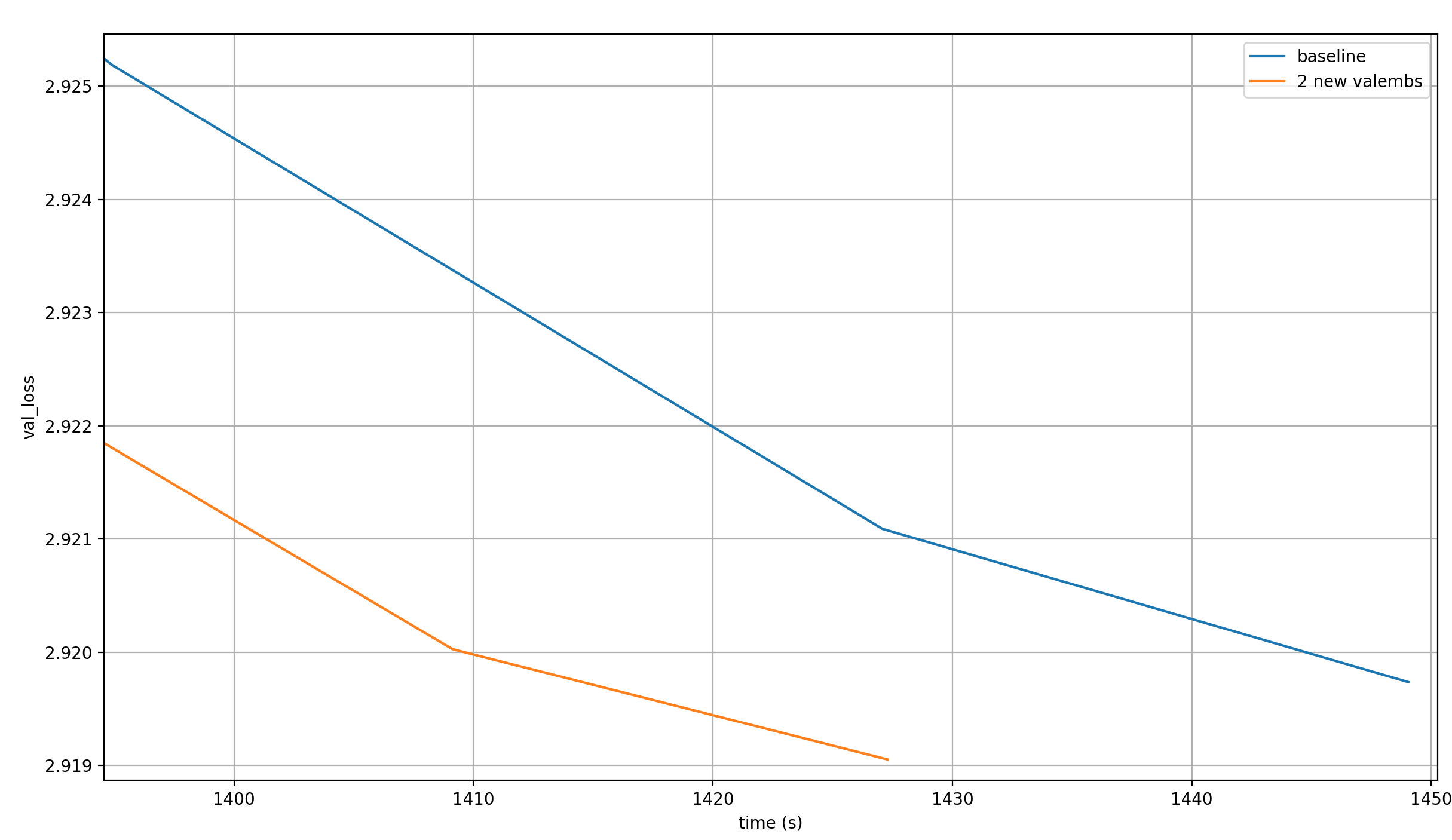

I re-ran the baseline, because I slightly changed the compile flags and used a newer version of PyTorch. Here is a plot of the value losses over time, averaged over 28 runs for the baseline and 37 runs for the record:

With the two additional value embeddings, the model reaches the target loss in ~21 fewer seconds.

A note on the averaging: I very simply averaged the loss for each training step, and independently averaged the time taken at each training step, and then plotted the loss over the training time. That’s not 100% mathematically correct because I’m averaging losses that happended after different amounts of time, but the averaging of the times should mostly make up for that, so the results are still valid (especially considering the large margin with which the record is set).

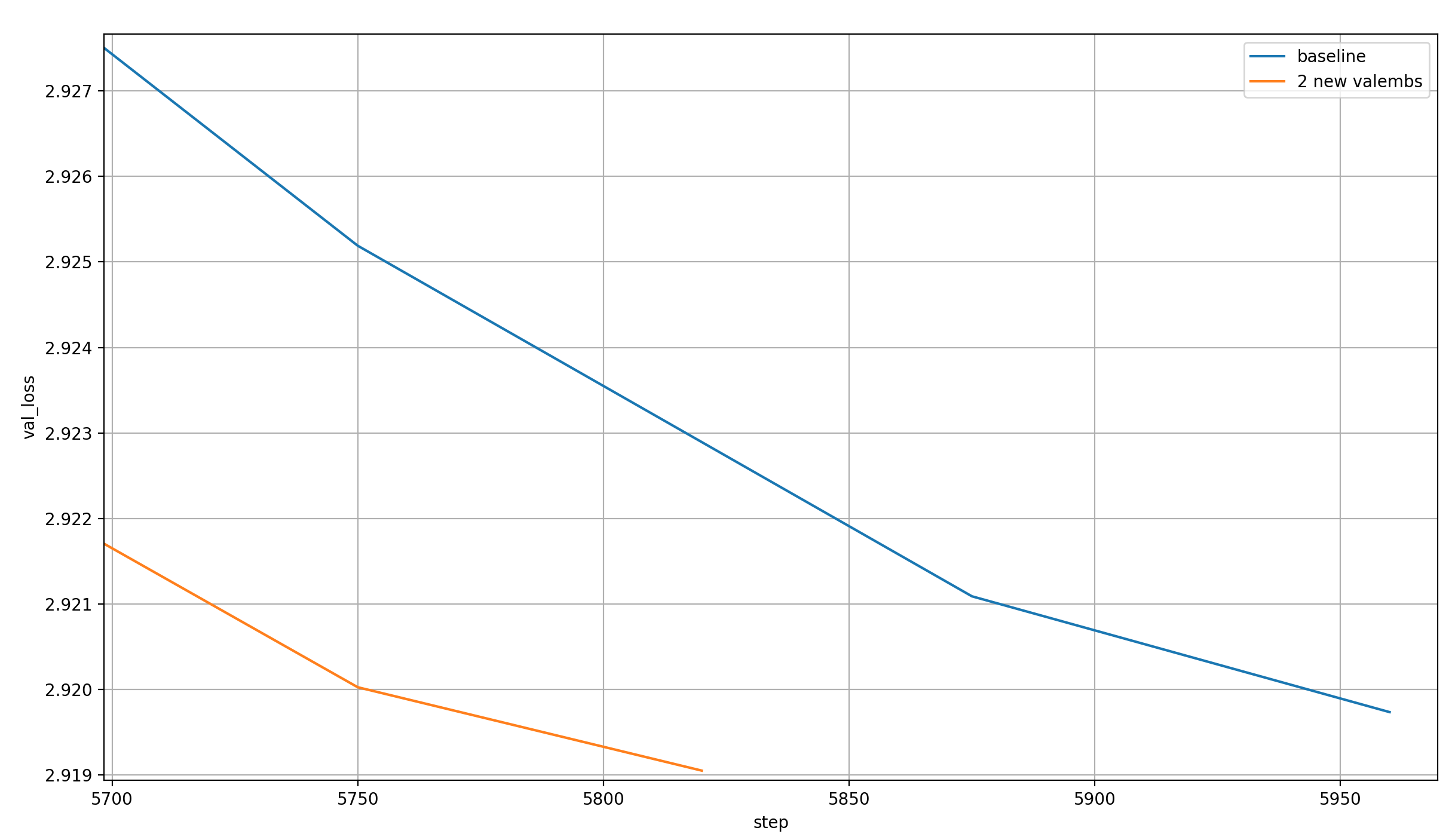

The record plot ends earlier because I ran it for fewer steps, 5820 instead of 5890, so all the benefit comes from improved per-step learnability. The per-step time is slightly increased by the new embeddings, as expected. Here is a plot of the validation losses over the steps:

I clearly could have stopped earlier, but I wanted the record to be rock-solid, because it is a requirement for an official record to show that the final validation loss of the runs is below 2.92 with a very high probability.

Here are the final validation losses over all 37 runs that I’ve performed:

[2.919612, 2.919458, 2.918941, 2.917664, 2.91856, 2.919706, 2.919218, 2.918082, 2.919345, 2.920486, 2.919293, 2.917286, 2.921162, 2.919861, 2.917587, 2.919488, 2.919955, 2.919172, 2.919245, 2.918839,

2.918381, 2.919301, 2.917944, 2.919178, 2.918395, 2.920141, 2.918754, 2.918432, 2.919958, 2.91978, 2.919916, 2.919711, 2.918025, 2.919342, 2.920571, 2.917387, 2.919093]

And here are some simple statistics about those losses:

- Mean: 2.919 ± 0.001

- Median: 2.919

- Min: 2.917

- Max: 2.921

The probability of the average final loss being below 2.92 is ~99.99995%.

Adding value embeddings

What happens if we add more than two extra value embeddings?

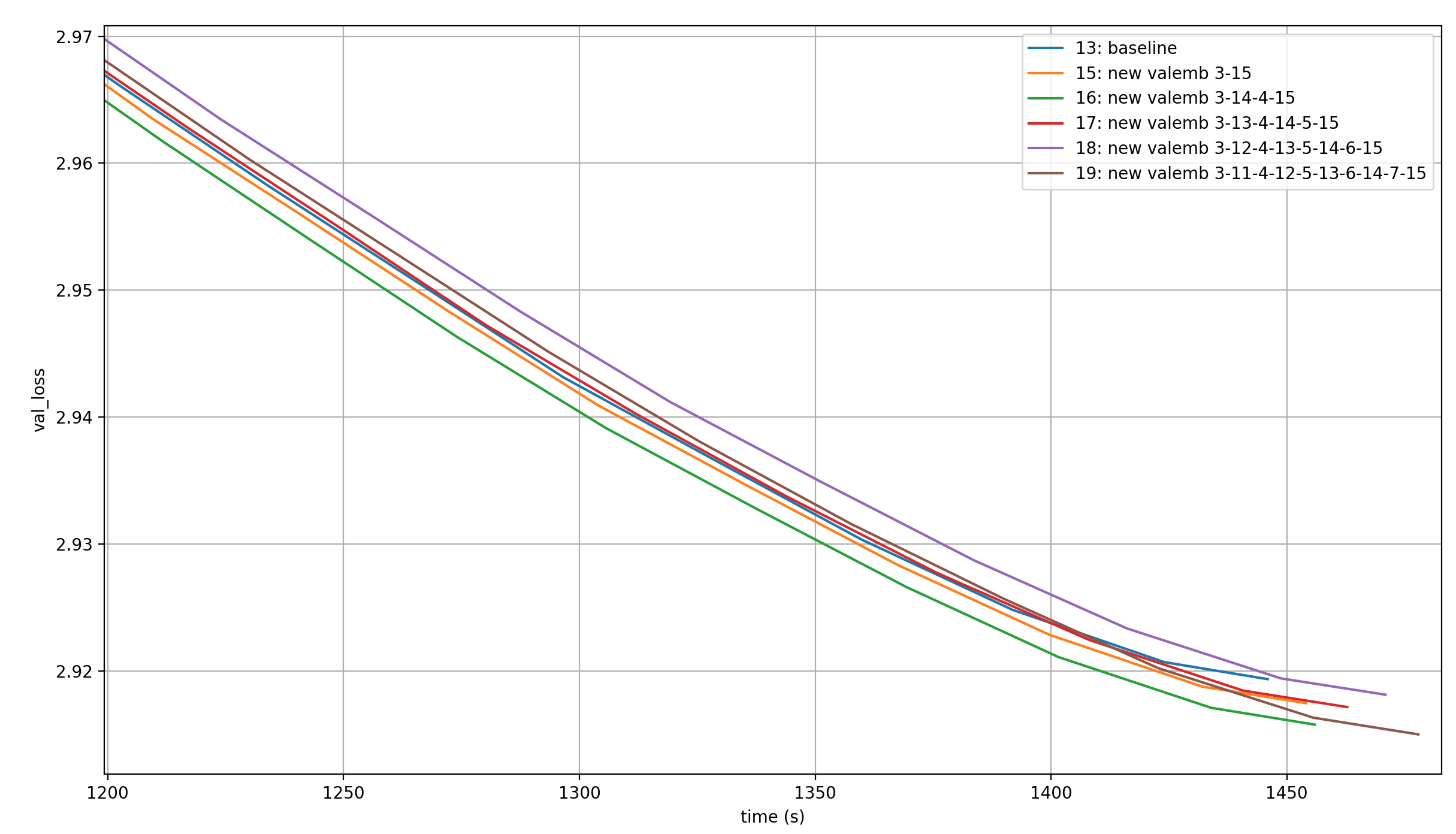

In the following plot, we see the validation losses over training of runs with a total of three (baseline), four (see above), five, six, seven, and eight value embeddings, each shared like in the baseline (so applying the n value embeddings to the first n layers, and to the last n layers again in the same order). That means that the one with the most value embeddings applies one value embedding to each layer in the model (except layer 7 which is attention-free).

These plots are for only a single run each, so the exact timing and loss values might be off, but we can definitely see trends.

Here is the order in which the runs cross the 2.92 loss-barrier, which is the target of modded-nanogpt medium:

- 2 additional value embeddings (1410 sec ~= 23.5 min)

- 1 additional value embeddings (1422 sec ~= 23.7 min)

- 5 additional value embeddings (1425 sec ~= 23.75 min)

- 3 additional value embeddings (1428 sec ~= 23.8 min)

- 0 additional value embeddings (1436 sec ~= 23.9 min) (baseline)

- 4 additional value embeddings (1444 sec ~= 24.0 min)

However, these times will of course vary over different training runs, and occur only in the last ~50s. I’m curious how the loss behaves in the time before that, because it might tell us more about what setting is consistently the best. This is the order from best to worst:

- 2 additional value embeddings

- 1 additional value embeddings

- 0 additional value embeddings (baseline)

- 3 additional value embeddings

- 5 additional value embeddings

- 4 additional value embeddings

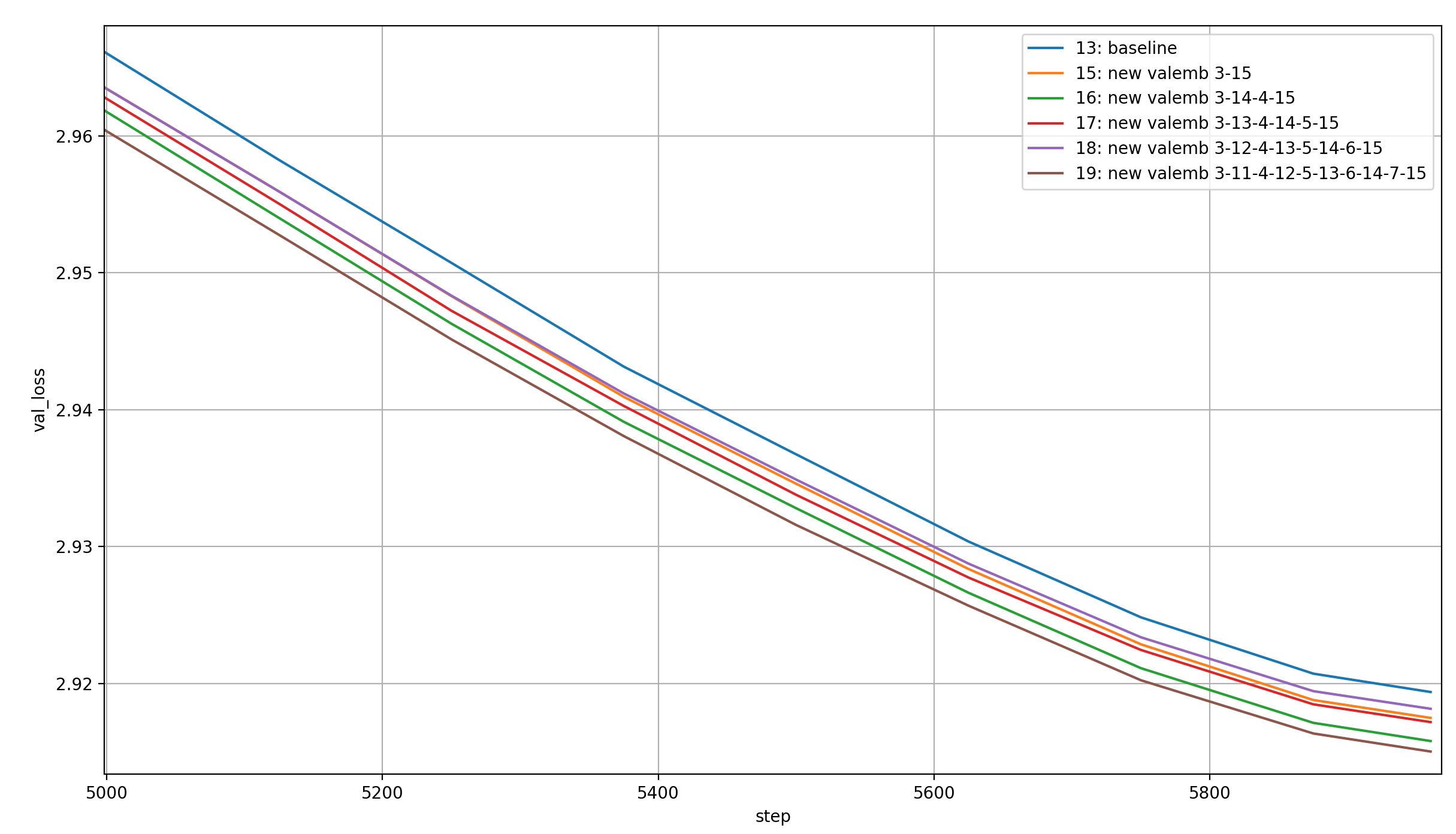

Let’s see if adding more and more value embeddings consistently improves the amount that is learned per batch, by plotting the loss over the training steps:

This seems almost monotonous, except for adding four additional value embeddings, which is the worst. Here is the order in which they cross the threshold:

- 5 additional value embeddings

- 3 additional value embeddings

- 2 additional value embeddings

- 1 additional value embeddings

- 0 additional value embeddings (baseline)

- 4 additional value embeddings

I would interpret this as “more value embeddings lead to more learning per step”, but the training run when I added 4 additional value embeddings was an outlier. I assume it would fit in nicely with the others in the trend if run multiple times.

If that’s true, then the 4 additional value embeddings also slot in nicely in the timed order, which would be (from best to worst): 2-1-0-3-4-5.

If that’s correct, then for one and two additional value embeddings, the additional loss reduction per step dominates over the additional per-step time, while above two additional value embeddings, the effect reverses.

Removing value embeddings

If adding value embeddings helps performance per time-step, then removing them should hurt them. Nevertheless, my investigations on different learned scalars in modded-nanogpt had led me to wrongly suspect that it should be possible to remove value-embeddings without hurting performance much.

Specifically, I thought that removing them in the early layers would be possible without a performance loss, because that’s where their effects are strongly suppressed. This would of course speed up the runtime because it would avoid some computation (though only a small amount).

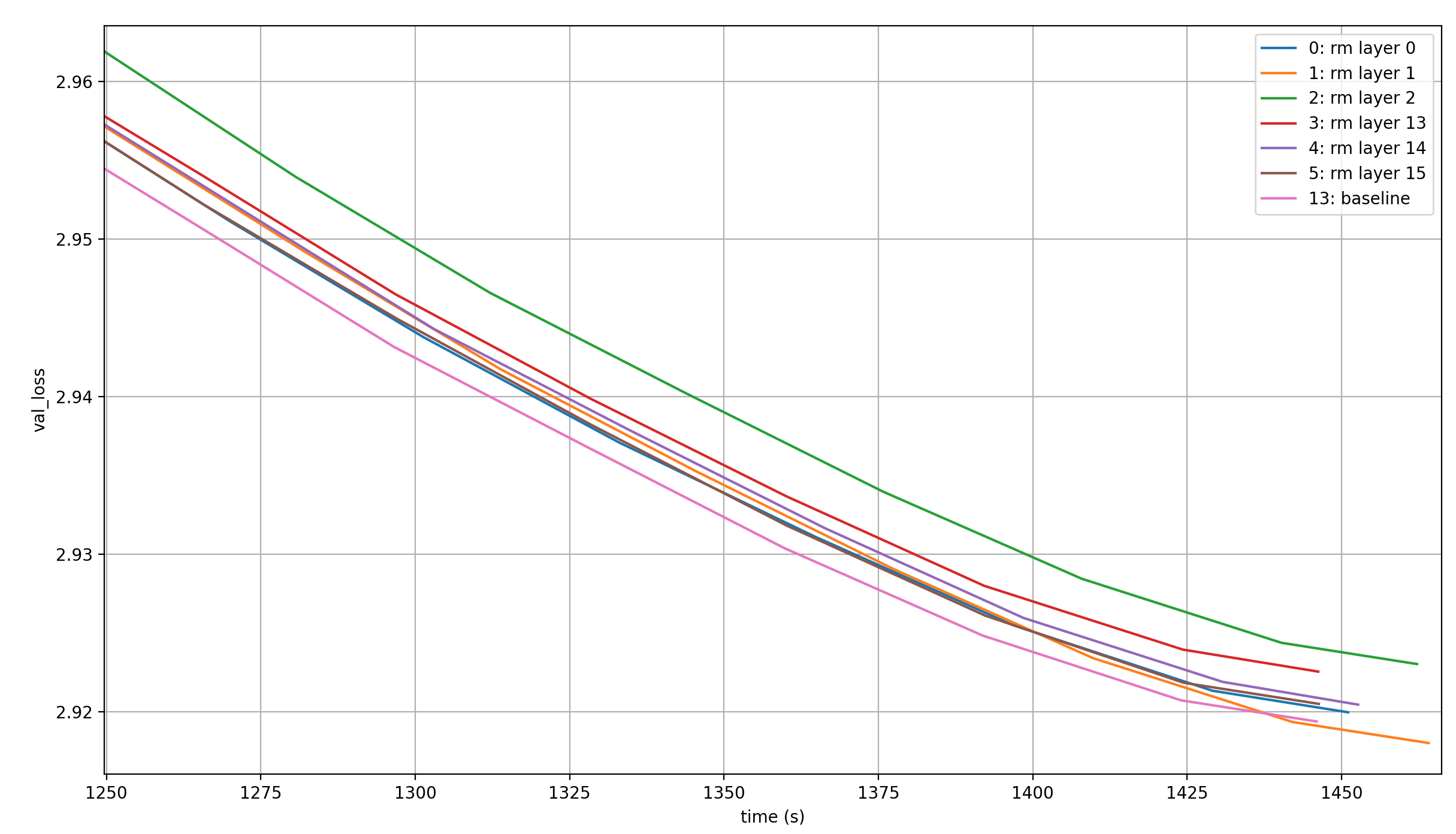

So here are the results of those experiments, starting with the removal of single value embedding.

To be clear, I don’t remove an embedding-module; I simply apply the value embeddings of one of the embedding-modules to one layer less. For example, “rm layer 0” means that one value embedding-module applies its outputs only to layer 13, but the others still each apply their outputs to two layers each.

These are the resulting loss curves when one layer doesn’t receive its value embedding:

None of them is as good as the baseline. However, the ordering of results is interesting. Keeping mind that random noise is a big factor here, it seems the order of removing value embeddings from worst to best is 2-13-14-15-0-1. That’s confusing.

Removing layer 2 is the worst by far? But the other two early layers are of almost no importance? That’s strange, and it makes me wonder what would happen if we shifted the value embeddings to slightly later layers; so instead of layer [0, 1, 2, 13, 14, 15] we’d have layers [1, 2, 3, 13, 14, 15] or [2, 3, 4, 13, 14, 15].

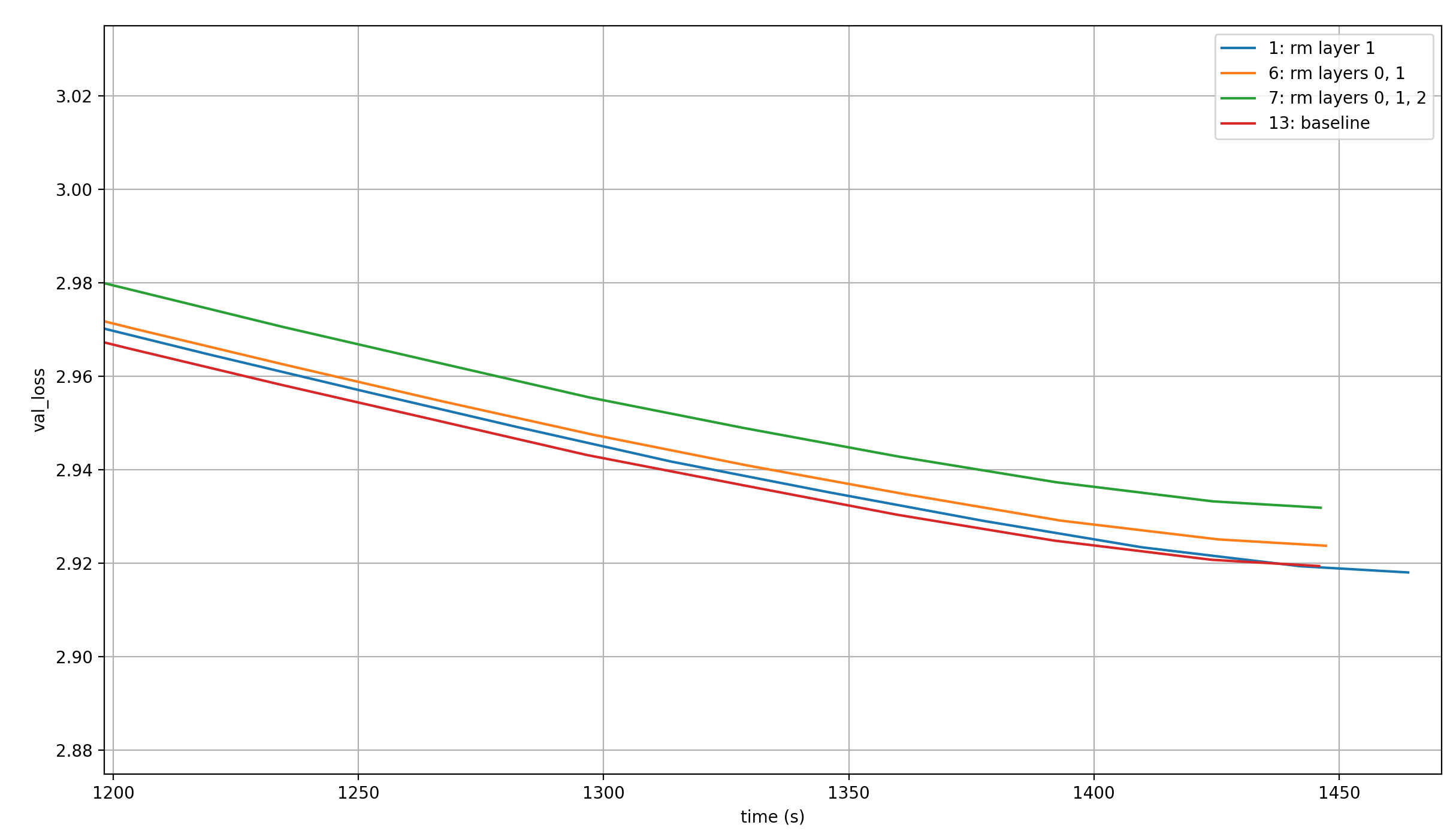

Before that, let’s look at what happens if we remove multiple layers at once though. First, removing layers 0 and 1, and layers 0, 1, and 2.

Again, no value embedding-module is removed for this, because they are shared with the value embeddings at layers 13, 14, and 15, and those remain; they are simply not applied to the marked layers. For comparison, I’ll throw in the baseline and the best performing run from before (so only layer 1 removed):

The two conclusions I can draw are that (1) the early value embeddings are definitely valuable and (2) the more of them are removed, the worse the result.

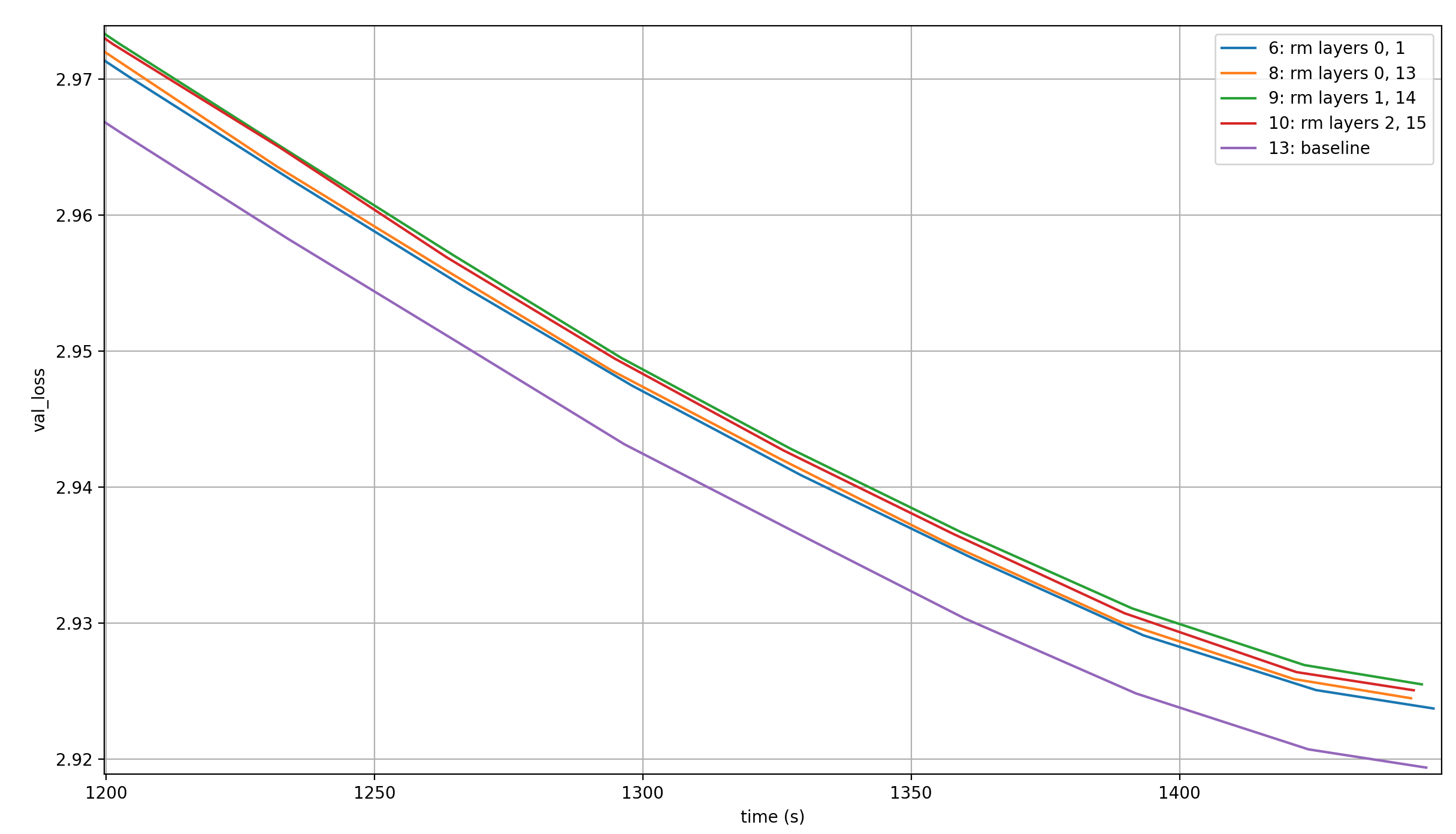

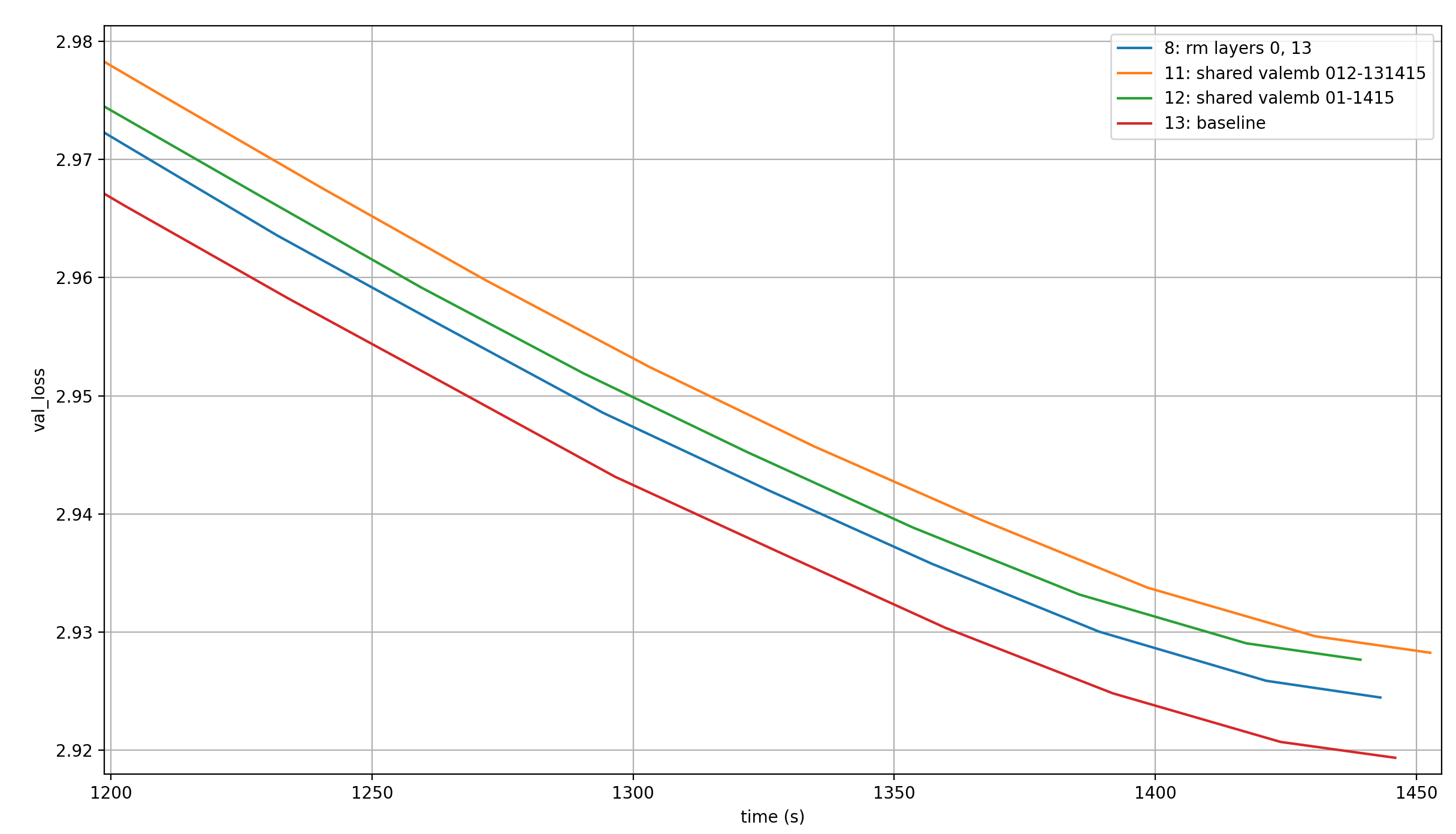

How about removing a full value embedding-module? Meaning removing the shared value embedding from layers 0 and 13, or 1 and 14, or 2 and 15. Here, I use two baselines:

- The original baseline with three value embedding-modules, each supplying embeddings for two layers; this is the obvious baseline

- Removing layers 0 and 1; this is a baseline because the same number of layers receive a value embedding as they do when a full embedding-layer is removed

These are the results:

Removing a full value embedding seems to be worse than not sharing its weights.

There is a limitation to these results, though: removing a full value embedding-module removes value embeddings from one early and one late layer, but my baseline removes value embeddings from two early layers only. As we’ve seen before, this might have a big effect. I haven’t run any experiments looking at, for example, removing the value embeddings from layers 0 and 14, or 1 and 13, etc., but those would be better comparisons. Nevertheless, it does seem like the parameters of the value embedding-module are missed.

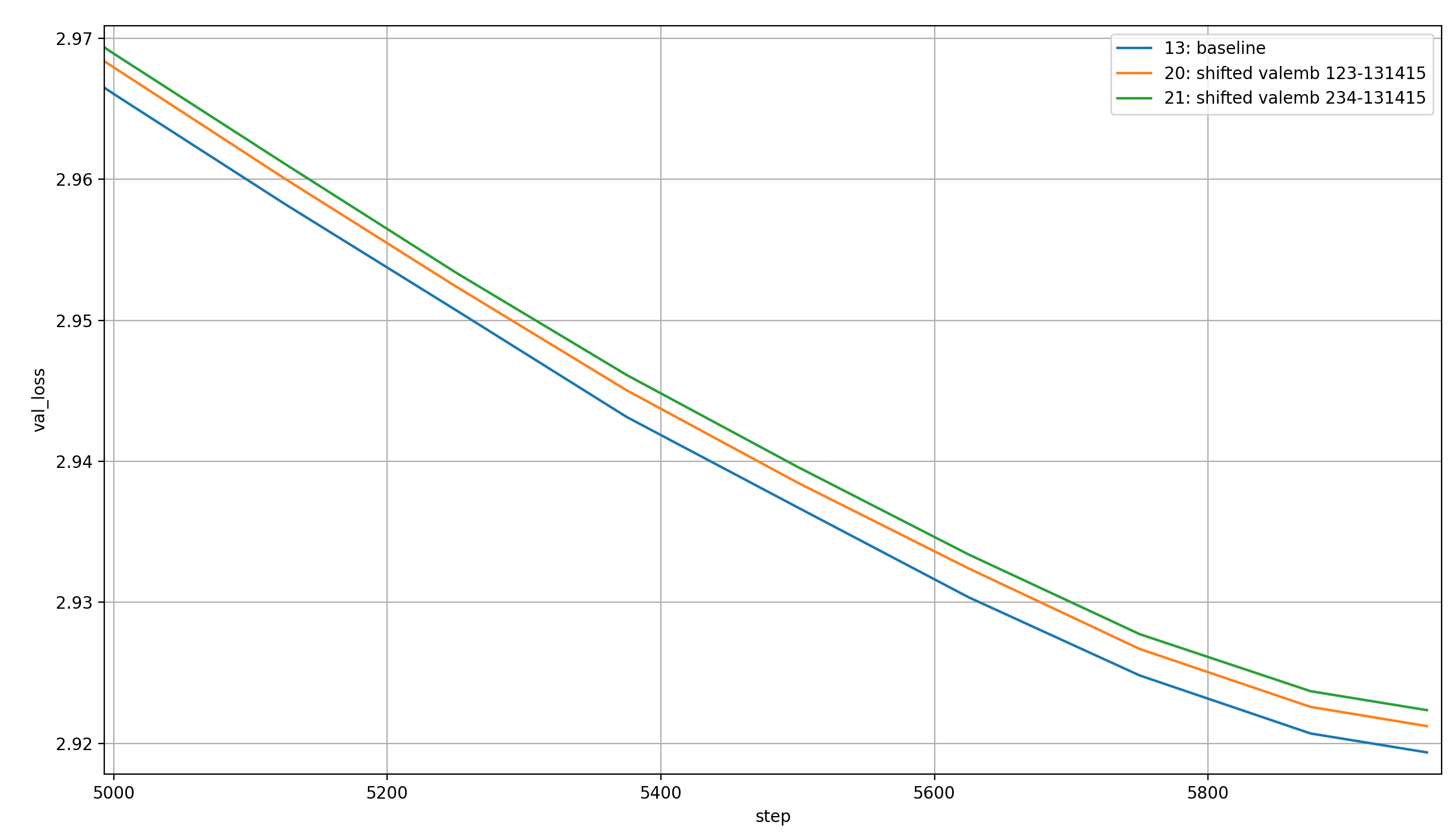

Shifting value embeddings

As discussed above, it might be interesting to shift the value embeddings from the early layers to slightly later layers. Let’s see this on two examples, where we use the value embeddings on layers 1, 2, and 3 or 2, 3, and 4 instead of 0, 1, and 2. In other words, we shift the early value embeddings to one or two layers later each.

There were some pretty extreme differences in timing between these runs, but I believe that those were due to random chance / GPU issue, so I will just plot them over the steps:

The shifted value embeddings seem to lead to worse results than the non-shifted ones, and moreso the more they are shifted.

Sharing value embeddings differently

I did wonder if the structure of sharing value embeddings across many layers (so layer 0 and 13 etc.) is optimal, or if we can share them differently.

My first experiment involved limiting myself to two value embeddings, which were shared in the following ways:

- Layers 0&1 and layers 14&15 share a value embedding each; so in total, we have removed one value embedding-module, but still apply the outputs of the remaining modules to two layers each

- Layers 0-2 and layers 13-15 share a value embedding each; so we again lose a value embedding-module, but apply each output to three different layers

The point of experiment (1) is to see if it makes a difference if we share embeddings between early and late layers, or if it’s also fine to share embeddings between early layers, and (separately) between late layers. The best baseline to this is the run where I removed the value embeddings from layers 0 and 13, because this also removed a full value embedding-module, and applied the resulting embeddings to a total of four layers. The only difference is that they are shared between distant layers.

The point of experiment (2) is to see if we can make up for any performance hit from the removed embedding layer by sharing the embeddings more. The baseline is the original configuartion of value embeddings.

Here are the results:

When we remove a full embedding layer, it is better to keep the interleaved structure where the value embeddings are shared between early and late layers, not between adjacent layers. Additionally, it is worse to share the same value embedding between three layers than it is to share it between two layers, even though the toal number of parameters stays constant.

Another way of sharing the value embeddings is to invert the application of the value embeddings in the early layers. I performed this experiment with the full five value embeddings, over the same number of steps as my record.

Before, the value embeddings are tied like this:

- Embedding 1 is applied to layers 0 and 11

- Embedding 2 is applied to layers 1 and 12

- Embedding 3 is applied to layers 2 and 13

- Embedding 4 is applied to layers 3 and 14

- Embedding 5 is applied to layers 4 and 15

I thought it might be better to invert this like this:

- Embedding 1 is applied to layers 0 and 15

- Embedding 2 is applied to layers 1 and 14

- Embedding 3 is applied to layers 2 and 13

- Embedding 4 is applied to layers 3 and 12

- Embedding 5 is applied to layers 4 and 11

This did not work though: over 17 runs, the mean final validation loss is 2.9196, compared to the 2.9194 without this change. This is a tiny, tiny bit worse, which means to me that the edit either changes nothing or makes things worse (though it’s hard to tell with such small differences).

Conclusion

Value embeddings are a powerful way to add bias to LLMs. In the case of the modded-nanogpt medium speedrun, adding two in the pattern of the existing value embeddings leads to a new world record, reducing the runtime by ca. 21 seconds.

The original pattern of applying the same value embeddings in the same order in the first and last few layers seems optimal.